Transactional analysis is a body of knowledge that can help us better understand our interactions with others and with ourselves. In this post, I share three models that can expand our awareness and offer some insight into the areas of our behaviour that seemingly occur automatically.

Parent - Adult - Child Ego States

This first tool is often called the PAC model. It is split into three main sections: Parent, Adult and Child. These are ego states and are no reference to our age or role in society. I will explain each state individually.

Parent: These are traits and behaviours that have been learned from the parent figures in our lives. Either our natural, birth parents or any role model who has influenced us to behave in a certain way.

Adult: As adults we choose how to respond in the present moment. From a position of awareness, we can choose to respond with any of the ego states from the Parent and Child sections. The important distinction here is that we are consciously choosing how to act. We are not reacting unconsciously.

Child: These are our felt experiences and responses to the things that have happened to us. The unconscious behaviours we have developed in response to our treatment by others over the course of our lives.

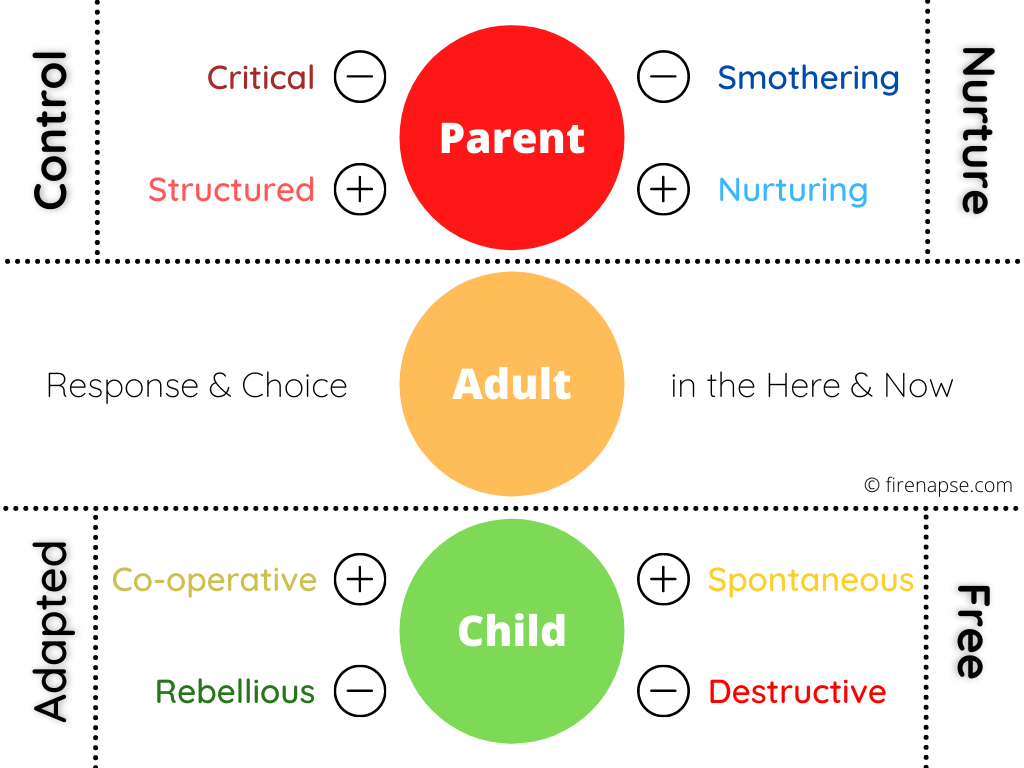

The diagram below displays these states and shows how each one can be expanded to offer a deeper insight into who we are:

The Parent state is split into two elements, Control and Nurture. Each of these are split into positive and negative qualities. The Child state is also split into two elements, Adapted and Free, and then each of these are split into positive and negative qualities.

The states often trigger one another unless there is conscious intervention. For example, when someone imposes structure or offers unsolicited feedback or criticism from a parent state, we can default to responding from a co-operative or rebellious child state.

Parent States

Controlling Parent

Our controlling parent is a reflection of the environment we experienced growing up. The positive quality of this element is structure, whilst the negative is critical.

Structure is important because it sets expectations. We know what we expect of ourselves and we often project those expectations on others. When structure and feedback are administered without thought they can become critical. Our critical parent is the part of us that tells us off when we don’t do something right. It speaks the inherited words we heard while growing up. Structure makes things happen and constructive criticism helps us grow.

Nurturing Parent

Controlling parent is focussed on achieving external things and doing them right. Nurturing parent is there to help us grow internally. Nurture builds strength and resilience and comes from a place of love. But too much nurture can smother the child and leave them ill equipped to deal with reality.

We nurture others by helping them grow and picking them up when they fall. We nurture ourselves through healthy self-care and taking action to look after our physical, mental and emotional wellbeing.

Child States

Adapted Child

Our adapted child decides how we respond to rules and structure. When we agree with the rules and structure, we co-operate with systems and others, when we don’t agree, we rebel.

Co-operation is built on trust and when that trust is betrayed, the temptation can be to rebel. When we agree to do a job we agree to follow the rules and standards required of that job. Our adapted child can start to rebel when we see others doing less than us or when we see others breaking the rules that we are sticking to.

Internally, if we impose too rigid a structure on ourselves, or make promises to ourselves that we don’t keep, we can start to rebel and cease to follow the instructions of our internal structured parent. Recognising this interplay between the different parts of ourselves can help us to adapt better to our situation, rather than blindly following the rules we have set for ourselves.

Free Child

Our free child is the source of our creativity. When we have space and permission to be spontaneous, we create and flourish. When we feel trapped and confined, we can become destructive.

Our free child expresses itself best within the confines of structure. Some rules are there for a reason, to protect us and others. Creativity needs a container in order to produce something relevant to the situation.

The Adult State

In the adult state, we posses the awareness to consciously choose how we are behaving. We can balance the interactions with ourselves (managing self-criticism and turning it into structured feedback) and with others (proactively choosing where we are expressing ourselves from, rather than reacting to people and situations).

We recognise that our internal state is always in flux and that our character is formed from a combination of our learned behaviours and felt experiences.

Fundamentally, in the adult state, we give ourselves permission to be more than one thing. We observe ourselves with curiosity and practise compassion to heal the wounds that we find.

Key Takeaways

- The ‘Parent Adult Child’ model applies to our interactions with others. These interactions can often be a reflection of the internal interactions we have with ourselves. For example, if we are overly-critical of others, it is likely that we hold ourselves to high standards and criticise ourselves when we don’t meet them.

- Our ego state is always shifting. Our character is formed from learned behaviours and felt experiences. The origins of most of these have long been forgotten.

- Change, therefore, is not a case of learning new behaviours, it is a case of unlearning the thoughts and feelings which constrain us. This model can help to name the parts of ourselves that take us away from being a proactive adult that responds to the present moment.

- There are always two parties in any interaction. The one who speaks and the one who listens. Change happens when we focus on adjusting both of these voices. We can change how we speak and we can also change how we interpret what we hear. This goes for both our communications with others, and for our internal dialogues with ourselves.

The Drama & Empowerment Triangles

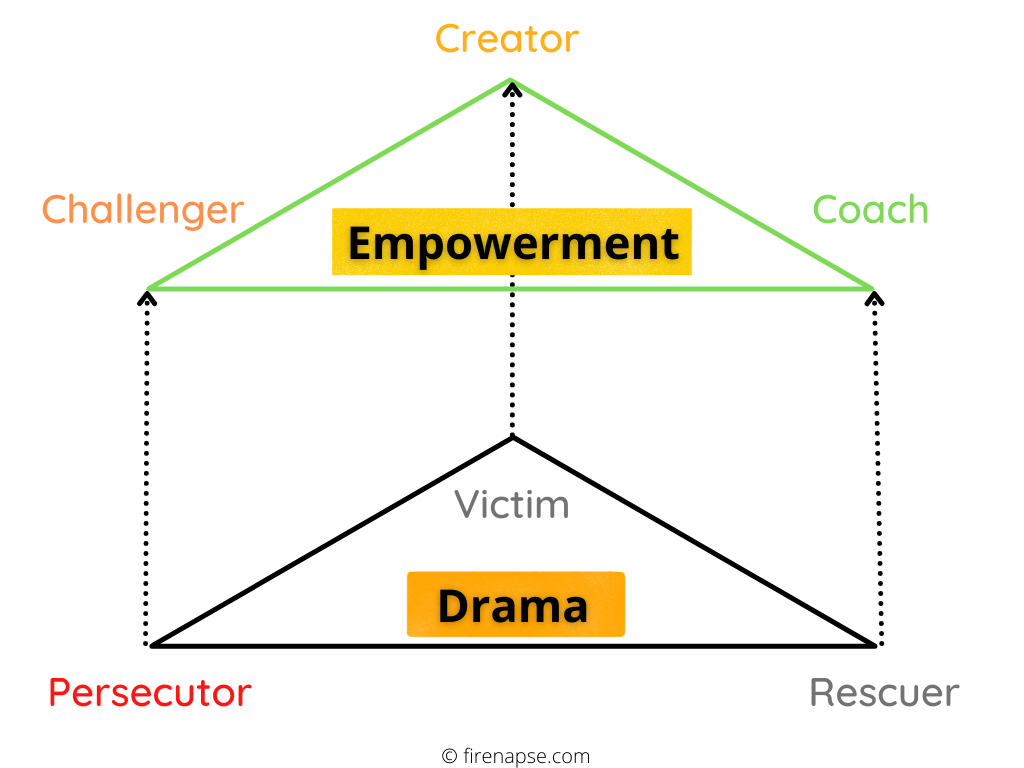

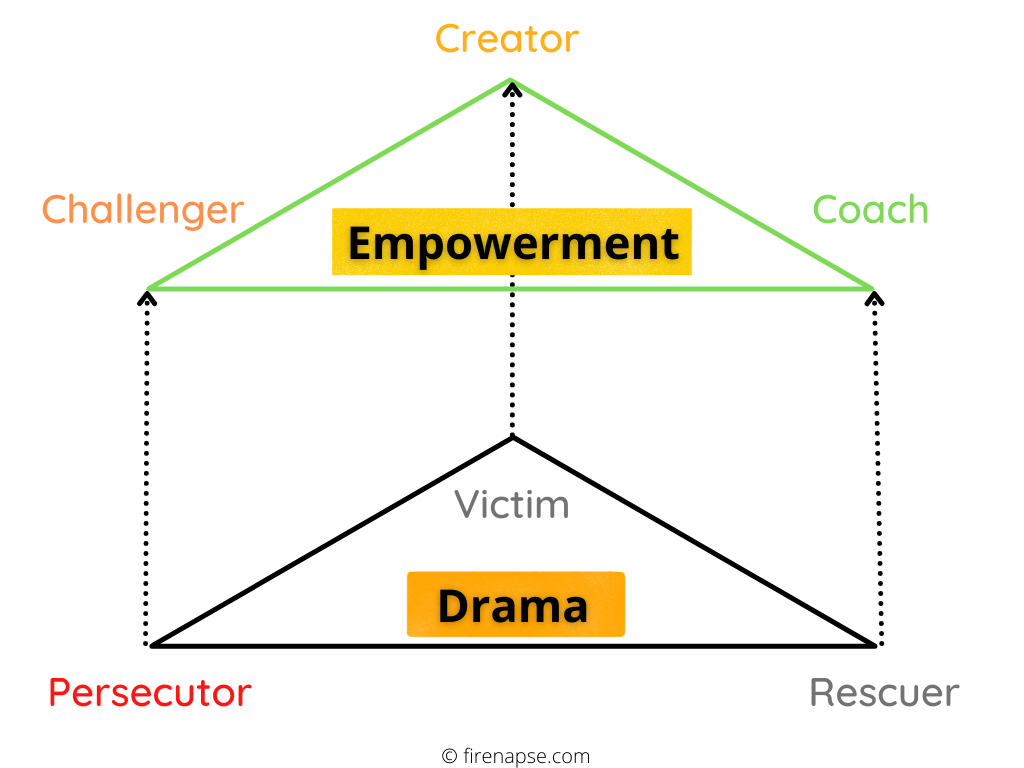

This next model is attributed to Stephen Karpman and consists of two triangles: the Drama triangle and the Empowerment triangle. Each triangle has three states, one at each of its corners.

Generally, the Drama triangle represents the states we wish to avoid. The Empowerment triangle offers three alternate states that are a direct evolution from the corresponding Drama states.

We can see that the Victim state is elevated to the Creator state. The Persecutor state is the negative representation of the Challenger state. And the Rescuer state is transformed into the Coach state.

Here are each of these evolutions expressed in more detail.

Victim -> Creator

As a victim, we have no control over the situation. By stepping from this state into the role of creator, we take ownership of the things occurring in our life and are empowered to make positive choices.

Persecutor -> Challenger

As a persecutor, we tend to bully others or ourselves. Stepping away from that negative attempt to stimulate change, we can choose to challenge ourselves and others in a productive way instead.

Rescuer -> Coach

As a rescuer, we are always trying to solve other people’s problems for them. We may struggle with boundaries and this can have a negative impact on our wellbeing. Our attempts at helping others can actually cause them to push away from us. As a coach, we ask questions and offer support to help people find their best solution, not ours.

The OK Corral

In this final model, we explore how we view ourselves in relation to others. In each box you will also see the interaction expressed with reference to the Parent, Adult, Child ego states.

Our ideal state is the top left hand corner, ‘I’m OK, You’re OK’. Here we speak to others as equals, feeling neither inferior nor superior to them.

Issues can arise when our interactions fall into the other three boxes.

In ‘I’m OK, You’re Not OK’ we may see ourselves as superior to others and talk down to them as if they were a child. Here we are adopting a critical or smothering parent state which can propel the other person into a child state. We also likely to be persecuting others because we perceive they don’t measure up.

In ‘I’m Not OK, You’re OK’ we are painting ourselves as inferior to others and will likely be overly deferential to them. Here we are the child looking to the parent to take care of us.

In ‘I’m Not OK, You’re Not OK’ things are pretty bleak. We are struggling to recognise any good in ourselves or others. This can lead to our interactions being dysfunctional and destructive.

In Summary

These models can be useful to identify interactions that are not yielding the desired result and help troubleshoot our feelings of discontent or discomfort. The fundamental truth in every interaction is every action has a reaction. By consciously changing how we act, we can start to influence how others react to us.

It can be more obvious to observe these patterns and apply the models in our interactions with others, but it is worth remembering that they also can shed light on the ways we interact with ourselves.

What effect does being overly critical or persecutory towards yourself have?

How does your mood and resulting behaviour change when you come from a place of structure, nurture and empowerment?